DNG Pros, Cons and Myths

Martin Evening is an accomplished studio photographer and author based in London. Martin’s book Photoshop for Photographers is in its 13th edition and his Adobe Photoshop Lightroom book has established itself as the encyclopedia on Lightroom. As an expert on Photoshop and Lightroom, Martin routinely encounters questions from photographers on topics like raw file formats. Below Martin tackles commonly asked questions and myths around Adobe’s openly documented DNG file format. I’d like to thank Martin for taking the time to explain this topic in such a clear format.

___

Without further ado, here’s Martin:

Is it wise to convert your raw files to the Adobe DNG format? If you are using Lightroom or Photoshop with Camera Raw, you have the option to convert your master files to DNG. In this article I want to focus on the benefits of converting, the reasons why converting to DNG may not always be ideal or necessary, as well as tackle some of the misinformation about DNG.

Why the need for the DNG format?

The DNG format was devised by Adobe in response to the growing number of undocumented raw camera file formats that are produced each time a new digital camera is introduced. The problem here is that these camera file formats are all proprietary to the camera manufacturer that specified them. To open such files you either need the camera manufacturer’s own raw processing software, or the ability to interpret the raw data using third-party software, such as Capture One, Camera Raw or Lightroom.

DNG as an archival format

Any of the 500‐plus types of raw files that are currently supported by Camera Raw and Lightroom can be archived using DNG. Some cameras even give you the option to save your capture images as DNG (including the latest Android smartphones). The DNG format is open standard, which means the file format specification (based on the TIFF 6 file format) is made freely available to any third-party developer. A number of programs other than Lightroom and Photoshop are able to read from and write DNG files. This supports the case for DNG as an archive format that meets the criteria for long-term file preservation that will enable future generations to access and read the DNG raw data. This should hold true in the same way regular TIFF files look set to be readable for the foreseeable future.

You will notice that whenever you import files into Lightroom, you have the option to convert to DNG. You can also do this by making a selection of photos in the Library module and choosing Library > Convert Photos to DNG. The only proviso is that the photos you import or select are in a raw format Lightroom recognizes. For now, there is no imminent need to convert everything to DNG since undocumented raw formats can still widely be read. However, in the long term, there are legitimate concerns about the suitability of storing raw files using undocumented file formats. Major operating system updates have been known to make older operating systems, and the software that runs on them, obsolete within a matter of a few years.

Therefore, continued support for undocumented file formats is directly dependent on future support for those applications. It is likely Adobe will be around 10 years from now, but photographers should really be asking themselves “what will happen in 50 or 100 years’ time?”

Validating the raw data

The DNG format contains a checksum validation feature, which can be used to spot corrupted DNG files. This is a useful feature for archivists as it allows them to check on the condition of their archived files.

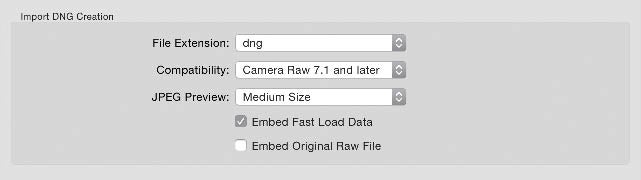

Faster performance

The DNG format allows you to enable Fast Load Data, which stores a standard-size preview in the DNG file. This enables faster loading when opening an image in Camera Raw or Lightroom. Having said that, Lightroom 6.3 now includes faster Camera Raw caching whereby the opening of proprietary raw files is now almost as fast as opening a DNG with Fast Load Data enabled. The DNG spec also enables image tiling, which can speed up file data read times when using multicore processors compared with reading a continuous compressed raw file, that can only be read using one processor core at a time.

Compact format

Raw files that have been converted to DNG tend to be smaller in size compared to the original raws. This is because the lossless compression method Adobe uses is generally more efficient compared to that implemented by most proprietary raw formats. In some instances the file size savings can be really dramatic.

Photo merged composites

If you are using Camera Raw 9 or Lightroom 6, you can create Photo Merged panoramas or HDR images that are saved as DNGs. Because of this they can retain the raw characteristics of the source images.

It is also worth pointing out that Camera Raw/Lightroom Photo Merge HDR are saved as compact, scene-referred 16-bit floating point TIFFs that can contain over 30 stops of image data. This is compared to HDR files that contain “baked” output-referred data that have to be saved as 32-bit TIFFs in order to store more than 30 stops of image data. Therefore Camera Raw/Lightroom HDR DNGs offer a more efficient workflow for HDR photography compared to other HDR-‐processing methods.

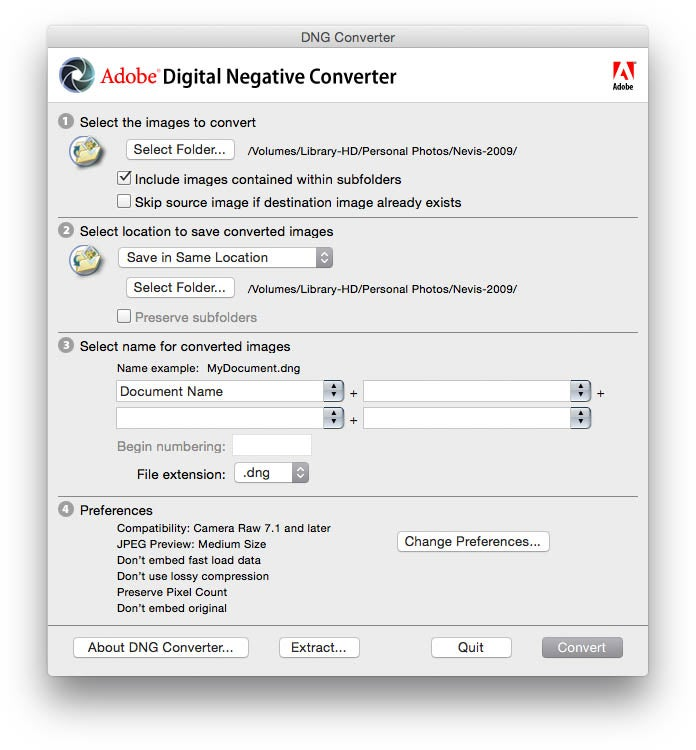

Keep up-to-date without upgrading

Camera Raw gets updated several times each year to provide support for the latest cameras and lenses. These updates are now only available to customers who are using Photoshop CC (since Camera Raw 9.2/Lightroom 6.2, ongoing Camera Raw support has ceased for CS6 customers). However, CS6 users, as well as those running older versions of Photoshop (or earlier versions of Lightroom) can use the DNG Converter program to batch convert raw files shot with the latest cameras to DNG and thereby keep their old software up-to-date.

DNG Cons

The time it takes to convert to DNG

Converting to DNG does have its downsides, most notably, the added time it takes to convert raw files to DNG.

DNG compatibility with other programs

While Adobe programs work well with the DNG format, there are other programs that support DNG, which do not. This has led to problems for some photographers who have converted to DNG. These are fixable through proper implementation of the DNG spec, but nonetheless it can be a hindrance to some users who are working with other raw processing programs. If you convert to DNG you do certainly lose the ability to process DNG files using the manufacturer’s dedicated raw processing software, unless you choose to embed the original raw inside the DNG. However, this can double the file size because you will be storing two raw files in one container.

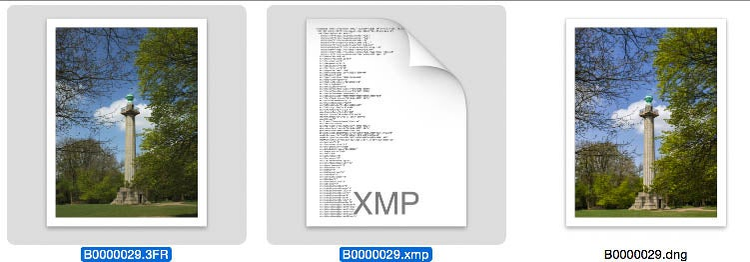

Backing up DNG metadata changes

If you save edit changes to the DNG files, this will slow down the backup process because the backup software will have to copy a complete DNG file instead of just the XMP sidecar files that otherwise accompany proprietary raw images. Personally, I believe it is better to let the Lightroom catalog file store the metadata edits rather than constantly overwrite the files referenced by the catalog. If you are in the habit of saving metadata edits to the files themselves as well, this is an important consideration, but you need to ask yourself, “In an emergency situation, where I might need to restore all my metadata edits, which is going to be the most up-to-date? The metadata that’s stored in the files, or the metadata that’s stored in the Lightroom catalog?”

DNG Myths

Converting to DNG changes the raw data

Whenever you open a raw image in Camera Raw/Lightroom the raw data is internally converted to the DNG format regardless of whether the file being read is a DNG file or not. In other words, DNG is the internal format for Camera Raw/Lightroom. If you can open an image normally using Camera Raw or Lightroom there will be no difference if you convert to DNG. It is true to say though that the raw data is converted in as much as the lossless compression used is different. The DNG format is based on the TIFF 6 spec, which is an industry standard file format.

The ability to read the raw data on a DNG is therefore only limited by the implementation of the DNG spec. When a DNG file is read correctly, the result will be identical to reading the proprietary raw format version the DNG was converted from.

DNG converts your files to an “Adobe Standard” color profile

When you import a raw file, Lightroom applies a camera profile setting as part of the import process. The same is true when you copy files to Bridge and open them in Camera Raw. The camera profile merely establishes the base settings ‘look’ for the imported files. By default, the camera profile is set to Adobe Standard. This applies a camera profile (created in-‐house by Adobe) that is specific to the camera the photo was shot with. If you prefer the default profile to be different, such as Camera Standard (to match the camera JPEG previews) you can do so by setting this as the new default.

When you convert a proprietary raw file to the DNG format it preserves the colors of the original raw file in the native color space of the sensor. Converting to DNG does not actually convert the data to an Adobe Camera Profile. “Adobe Standard” is simply an option for the default color rendition when interpreting that raw color data in Lightroom of Camera Raw. The camera profile information is included in the DNG metadata so it can be read by Adobe Camera Raw or Lightroom. The Adobe Standard camera profile is meaningless to other DNG-compatible software programs and is therefore simply ignored by them.

The DNG conversion process converts the raw data to something that works best with Camera Raw and Lightroom, which means other programs, are unable to interpret the raw data.

Other DNG-compatible programs, such as Capture One are able to read DNG files, just as they are able to read any other recognized raw format. How the raw data may have been previously read and edited using Camera Raw or Lightroom will have no bearing on another program’s ability to read the same raw data. This is because each raw processing program will have its own unique way of demosaicing the raw data and will allow you to apply image adjustments using that program.

It is not a good idea to convert JPEG images to DNG

The DNG format was originally designed with raw files in mind, but you can also use it to archive JPEGs, and here’s why. While it is true that converting a JPEG to DNG does not turn it into a raw file, there are very good reasons for using DNG as a JPEG container format. Lightroom allows you to import and edit JPEG files (such as those shot using a smart phone) using the same slider controls as you use to process raw files. If you save the metadata to a JPEG file via Camera Raw or Lightroom, the Camera Raw settings are saved to the file’s metadata so these settings can be read externally if you edit the original or a copy of the original file. If you choose to export a JPEG from Lightroom, it is all too easy for the Camera Raw metadata to be omitted. If you choose to convert your JPEG files to DNG, the Lightroom-applied settings will always travel with the master image and allow another Camera Raw/Lightroom user access to the settings applied to the JPEG. At the same time, saving as a DNG file saves a Lightroom-adjusted preview, so when it’s viewed in any third-party, DNG-aware program, the correct preview is seen, even if it doesn’t have the same edit controls as Lightroom or Camera Raw.

All photographs © Martin Evening. My thanks to Eric Chan and Tom Hogarty at Adobe for their assistance, researching this article.