Design more effective and inclusive conversations for Voice UIs

The adoption of voice technology continues at a rapid pace. Smart speakers are expected to soon be the top-selling electronic product for consumers (according to Strategy Analytics), and voice interactions are becoming a part of our day-to-day routine.

But as voice-enabled devices are getting more sophisticated, the user experience of these interactions is more often leaving us frustrated or clueless as to what to do next. Even worse, these devices' responses and actions can be biased and harmful. So, how do we improve them? Just like any other product or service, conversational interfaces need to be designed with ethics in mind from the start and follow a human-centered design approach.

For this article, we asked five experts in conversational design for their tips on how to create more effective, more natural, and more inclusive voice experiences.

Understand the context your voice experience will live in

Voice UX designer and strategist Maaike Coppens, currently chief design officer at conversational AI and chatbot agency GreenShoot Labs, stresses that conversations don’t exist in a vacuum and that they are indeed an exchange of information with a set of often unspoken rules and relationships in a given context. For the exchange to be effective, the understanding of that context is key.

Context exists on different levels: the environment (e.g. noisy, familiar), the situation (e.g. fun, delicate, in a group, alone), the user context (e.g. their experience, expectations), and the conversational context (e.g. first time use, previous interactions). To discover valuable information about all of these areas, user research of your audience — with a specific focus on mental models and language use — is critical.

“An excellent way to carry out that research is through speech shadowing,” Coppens explains. “It immerses the design team into the real-world environment and situation they’re designing for. For example, when you are creating an experience for a home improvement store, spend time talking to vendors and their clients on the floor and focus specifically on how they formulate questions and designate items. It can prove to be very insightful!”

Provide multiple voices with different genders and ethnicities

Cathy Pearl, a design manager on Google Assistant, author of “Designing Voice User Interfaces”, and member of Adobe’s Design Circle, recommends thinking about both the output of the system as well as how it handles input.

On the speech production side, she advises ensuring a wide representation of voices, whether using recorded voice actors or text-to-speech-synthesized computer voices.

“Go beyond the default of using a female — usually young and white-sounding — voice,” Pearl suggests. “Offer different genders and different ethnicities for a user to choose from. In addition, don’t assign one voice as the default. Expose your users to different voices, but allow them to change it. More companies are starting to offer a diverse selection of computer-generated voices, and it’s important to normalize hearing a wide variety.”

Image credit Google.

Give consideration to a variety of cognitive styles

On the speech recognition side, Pearl highlights the need to allow for different cognitive styles of the people interacting with your system. Not everyone speaks the same and uses the same order of providing information, the same number of words, or the same amount of small talk.

“If your conversational agent requires users to respond in only one way, you won’t be able to assist everyone equally,” Pearl cautions. “Some people like to provide all the information up front, such as ‘I need to check on my order from last night, which is number four six three zero,’ whereas another person might start with ‘Hi, I need to check an order,’ or even ‘Hi, how are you?’”

Also don’t skimp on conversational repair. If someone says something your system didn’t understand (which, Pearl points out, will almost always be the case), don’t fall back on generic error behavior like “Sorry, I didn’t understand”. Pearl recommends tailoring your error prompts to the current context, providing escalating levels of error, and offering to talk to a human if possible.

Aim for authentic representation of diverse dialects

Product architect and strategist Preston So, author of “Voice Content and Usability”, agrees that building inclusive conversations for voice user interfaces isn’t just about the identities and lilts you hear in synthesized speech. As a trained linguist, So finds many conversation designers, whether due to the tendency toward monolingualism in our societies or due to anglophone privilege, don’t realize or recognize that people often switch between different dialects and languages — sometimes even mid-sentence — while expressing themselves in real-life situations.

“Conversation designers must be attuned to the ways in which their intended users speak themselves and especially be aware of sociolinguistic phenomena like code-switching and diglossia,” So points out.

In code-switching, speakers swap between dialects depending on who they’re interacting with. For instance, usually out of necessity, Black Americans toggle between African American Vernacular English and "white-passing" dialects, while queer and trans communities switch between LGBTQIA+ and "straight-passing" modes of speech. Meanwhile, languages like Portuguese and Greek display high degrees of diglossia, where depending on the situation, speakers use formal or informal versions of the language that diverge considerably in grammar and lexicon.

So recommends that designers looking to implement omnichannel solutions for conversational interfaces straddling both written chatbots and spoken voice bots make sure they really understand their users. Designers should pay close attention to how buttoned-up or colloquial their audiences expect their interfaces to sound.

Distinguish clearly between informational and transactional conversations

So also stresses that these concerns are particularly important in informational (or what chatbot designer Amir Shevat calls topic-led) voice interactions, which remain relatively rare compared to transactional (or task-led) voice interactions.

“Establishing trust and authority by designing conversations in ways that resonate with audiences of disparate lived experiences is a much greater challenge for voice interfaces that deal with information and content in lieu of transactions and commerce,” So argues. “And designing conversations that supply information instead of handling transactions is difficult precisely because of the nuances of delivering information in a time-efficient, and conversationally legible — or listenable — way.”

Account for stress situations and explore potential for harm

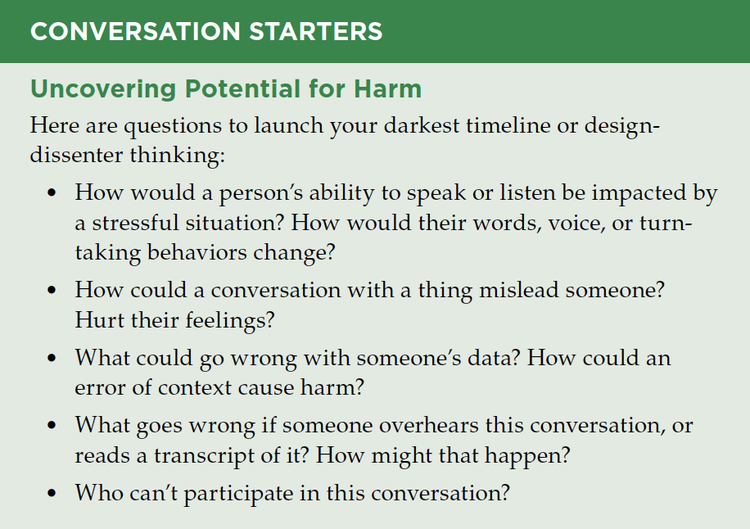

Conversation designer Rebecca Evanhoe, co-author of “Conversations with Things: UX Design for Chat and Voice”, emphasizes that inclusive design practices aim to make sure a product is designed well for many people (Can everyone easily use it? Does it solve customers’ problems?) but that the flip side is taking time to ask how a product or feature might create problems or even harm people.

“People using the product will often be stressed out or frustrated, and this can interfere with their voices, the words they use, or how those words are delivered,” Evanhoe explains. “When teams don’t account for those changes, people who might need the product the most can be excluded when it doesn’t work for them.”

Some people using a product will even be using it with intent to harm. For example, lots of technologies can be used to stalk or gaslight people, most often women, and Evanhoe refers to Eva PenzeyMoog’s book “Design for Safety”, which covers these types of cases and warns how technology “at its least harmful […] results in frustrated users — at its most harmful, it can be a literal matter of life and death.”

“Teams can get far by dedicating time during product development to explore potential for harm, determine ways to reduce harm, and test solutions — just as you would any other important feature,” Evanhoe recommends.

“Conversations with Things” by Rececca Evanhoe and Diana Deibel includes a list of questions to help teams launch discussions around the harm a product or service could cause.

Translate with care and localize your content

One of the issues that Diana Deibel, design director at digital product design consultancy Grand Studio and the other co-author of “Conversations with Things”, regularly encounters in her work is the desire to shortchange translation.

“Often businesses want to simply run a conversation through an automated translation tool and spit out the new version of the conversation — voilà!,” she says. “Unfortunately, language — and conversation in particular — is not that simple. Conversation envelopes bits of regional dialect, cultural customs and humor, and more. Translations done without a local speaker miss the nuance critical to an authentic and accurate conversation. More importantly, they require a heavier cognitive load on the part of the listener to parse what someone is saying.”

On a very simplistic level, Deibel suggests considering a conversation in which a question about if you’ve been to the zoo is phrased like “To the zoo, have you been?” You know what the person is getting at, but it takes your brain a moment to understand it.

“If this happens again and again, it becomes too much work to continue the conversation and your brain begins to tune out,” Deibel cautions. “This becomes particularly problematic when someone’s experience is driven by conversation. To combat this issue, use human, native speakers for both translation as well as usability testing to ensure you’ve created a usable, authentic, and accessible conversation.”

Delivering compelling voice content that works for everyone

The technology that powers voice experiences is evolving fast. The next step is to really focus on the users and avoid the inherent and often unconscious biases that prevent voice experiences from being more natural and more authentic. It might not always be under your control as a designer but if you carry out extensive user research and testing that goes beyond empathy, you’ll have the tools to convince stakeholders of the benefits of more accurately representing the real world. As a result, more people will be able to hear themselves reflected in the technology they use and feel a stronger connection to your brand, service, or organization.